The App I Built That I Didn't Need

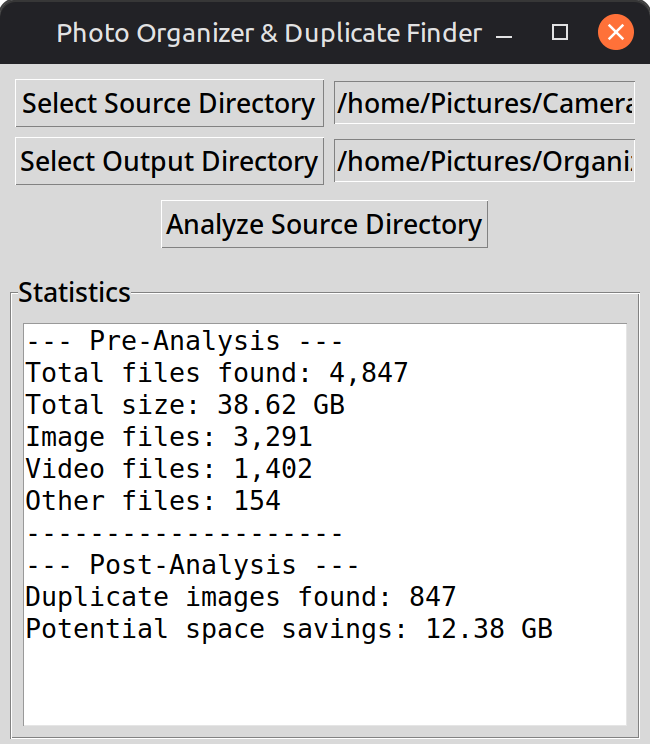

My first real project with AI assistance was a photo organizer. Not a script — an actual application. You’d pick a source folder full of unsorted photos, pick an output folder, and hit go. The app would read EXIF metadata from every image, rename each file by date taken (2024-03-15_14-30-22.jpg), organize them into year and month folders, separate out videos and files with no date, then scan everything with perceptual hashing to find near-duplicate images. Non-destructive — it copied, never moved the originals.

553 lines of Python across a CLI tool and a desktop GUI. Threaded processing with a progress bar so the interface didn’t freeze. Packaged into a standalone executable you could hand to someone who’s never opened a terminal. Built over a weekend in December 2025. The code is on GitHub if you want to see what a first project looks like.

I was proud of it. It solved a real problem. I had years of family photos scattered across drives with names like IMG_1108.MOV and IMG_1108 (2016_01_16 18_42_06 UTC).MOV — the same file copied five, six, seven times across backup drives that had been cloned and re-cloned over a decade. Multiple generations of “back up everything just in case” without ever cleaning up.

The Same Problem, Bigger

A few weeks later, I installed Claude Code and started building JARVIS — my home AI server. One of the first projects was a drive cleanup — the same problem, but bigger. Three external drives. Terabytes of accumulated files.

This time I didn’t build a GUI. I described what I needed and Claude wrote it: a three-pass duplicate finder that grouped files by size first (fast, no disk reads), then computed partial SHA-256 hashes on the first 64KB of size-matched files, then ran full hashes only on the partial matches. Inventory scanners, categorizers, Windows junk detectors, sync scripts — a full cleanup toolkit, built in a fraction of the time.

Across three drives, the scanner found 38,612 duplicate groups — files that existed in two, three, sometimes seven or more copies. One file appeared 30 times. Total wasted space: 578 GB. Nearly 26,000 files existed in three or more copies, accounting for almost 500 GB of redundant data by themselves.

The worst offender was a single 4 GB video file copied three times on the same drive — three different filenames, same content, 8 GB wasted on one file. The top 20 duplicate groups alone accounted for over 50 GB.

A decade of “just copy everything to be safe” had created a mess that no amount of manual cleanup would fix. I needed exactly the kind of tool I’d already built — except the version Claude and I built in January was faster, more precise for exact-match detection, and covered multiple drives instead of one folder.

The Part I Didn’t Expect

The drive cleanup toolkit was more powerful than the photo organizer in every way. But I didn’t need that app either.

After building JARVIS and getting comfortable with agentic AI workflows, I realized that most of what both tools did could be handled by a conversation. “Find duplicate files larger than 100MB on this drive” is a prompt, not a product. “Organize these photos by date taken” is a prompt. “Show me what’s eating space on the backup drive” is a prompt.

The photo organizer had a GUI with buttons, progress bars, and a trash confirmation dialog. The drive cleanup toolkit had three-pass hashing and formatted reports. Both were well-built tools that solved real problems. Neither one needs to exist as a standalone application anymore, because the AI that helped me build them can just do the work directly.

What Was the Point, Then?

Building the photo organizer taught me how EXIF metadata works, how perceptual hashing compares images, how to thread a Tkinter app so the UI doesn’t freeze, and how to package Python into a distributable binary. Building the drive cleanup toolkit taught me efficient hashing strategies, how to scan across mounted drives, and how to generate structured reports from file system data.

I use that knowledge constantly. Not by opening the apps — by understanding what’s happening when I ask an AI to do the same work. When I say “find duplicates on this drive,” I know what’s happening under the hood because I built it myself. I know why a perceptual hash catches near-duplicates that a SHA-256 hash misses. I know why you scan by file size first before computing any hashes. That understanding makes me a better collaborator with the AI, because I can tell when it’s doing something wrong.

I think a lot of early builders are going through exactly this arc right now. You create something to prove you can, and by the time you finish, the tools have moved past the thing you built. That’s not wasted effort. You won’t use the app. You’ll use everything you learned making it.

The apps were never the point. The understanding was.